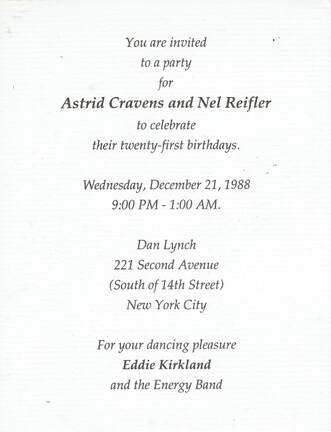

Eddie Kirkland was the pièce de résistance.

For thunking knocking funky rocking blues, I put Eddie Kirkland right up there with Howling Wolf and B. B. King but, unlike them, I had seen Kirkland live (adj.) at two or three roadside dives around Kingston and Newburgh, plus at a great gig to a packed crowd on a Saturday night at Speaker’s in the middle of New Paltz where, at that time, the State University of New York students were pretty hip.

Considering these venues, I figured that, unlike Howling Wolf and B. B. King, Eddie Kirkland might be affordable, but I was not only pleasantly surprised but a teeny bit nonplussed when over the phone (just to remind you: phones then were strictly audio devices) his agent and I agreed that Eddie Kirkland and the Energy Band would arrive at the party around eight‑thirty to set up, then play five sets from nine to midnight for $600 in cash, payable at the end of the gig.

The party was great. It was an Event, so how could it not be?—even though Eddie Kirkland never showed.

It was Eddie himself on the phone this time—the phone at the end of Dan Lynch’s bar around nine o’clock: he was stuck in a snowstorm in Canada and couldn't make the gig, but he had called a friend of his who would come over with his band and do it.

Except for the snowstorm in Canada, which was an intriguing touch, I wasn’t surprised, nor especially put out. That’s the way the cookie crumbles and, as I had learned long before, the more elaborate the cookie, the more prone it is to crumble here and there.

` The replacement band—Igor Mills and the Wheels (I just made that up; I don’t remember what the fuck their name was)—was one of those bands of young blues enthusiasts—90% white, 100% in college—who were good enough to have made it into the blues bar circuit. They got the music down pat, put on a great show and, helped along by the party having become a bona fide Event, seemed every bit as good as George Thorogood.

Dennis Winter was at the party where he met Eddie Kirkland. Eventually—typical of Dennis, with his gregarious charm—he got to know him pretty well, well enough to be Eddie’s chauffeur for a season, driving him around the South from gig to gig.

Dennis, a virtuoso story-teller, had some good ones about his peregrination with Eddie. For example: In a gap between gigs, Eddie decides to visit his ex-wife, who lives in a split-ranch in a development outside of Jacksonville. As Eddie gets out of the car he tells Dennis to keep the engine running. After a minute or so, the front door swings open and Eddie comes high-tailing it out, pursued by a woman in a white bathrobe with a knife.

The above story is fictional, based on just a couple of details I happen to remember from one of Dennis’ Eddie Kirkland stories.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Reader survey:

My fictionalization of Dennis’ story is

(choose a or b)

a) part of the process of history becoming myth, in which the

mortal Eddie is elevated to an avatar of The Hard-Driving Black

Blues Singer, something along the lines of Ulysses, who also was

known for comical hair-breadth escapes from angry women.

b) an example of how stories are forgotten and finally fade away.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Dennis Winter died last year.

~

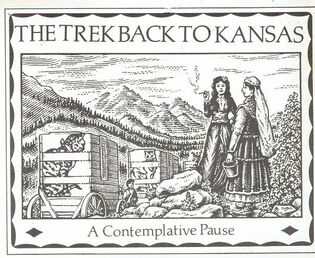

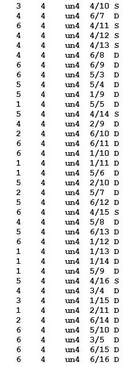

*Note on the picture.

Rendered from the image printed on Balkan Sobranie cigarette boxes.

(I have begun to think of myself as a stranger in a foreign country, and here it is, it’s happening again: I have to explain something that wouldn’t need explaining in my own country.

I’m not referring to geopolitical countries, but countries which, for a while anyway, occupy the same space at the same time. What makes them different is that their inhabitants cannot understand each other.

I am not saying that everyone in my country would recognize that somewhat esoteric image as being from Balkan Sobranie cigarette box. But most would recognize it as a commercial illustration dating from sometime before 1950. Some, taking note of the woman’s clothing and the landscape, might be able to place the scene somewhere between Greece and the Caucasus. Those who notice the cats would recognize it, for better or worse, as a collage. The word "Kansas" might puzzle some who, if they took the trouble, would probably settle on it being some reference to generic mid-America; only a few (so I discovered) would make the connection (which I had mistakenly thought to be pretty obvious) to the adventures of Baum's Dorothy.

The point is, everyone in my country knows something about that picture, and that’s enough for me not to have to explain it.

But the picture evokes nothing to anyone in this country (in which the newspaper of record once referred to Hungary as “a small East European backwater").

Are those supposed to be a couple of hippie chicks from the ‘60’s in peasant dresses smoking dope? or what?)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed