It took a deep internet search before I could find a picture of Peter Chamberlain. He doesn’t seem to have an admirer, or an academic who wrote a paper about him, among Wikipedia’s zillion editors, so there is no entry for him. He is mentioned in the Wikipedia article “Literature of Birmingham.”

W. H. Auden and Louis MacNeice also formed part of the remarkable wider group of writers and artists that formed in Birmingham in the 1930s around the Edgbaston home of the poet and classicist E. R. Dodds; the Birmingham Film Society; and Highfield, the rambling Selly Park home of the economist Philip Sargeant Florence and his wife, the journalist and radical Lella Secor Florence...

Also connected with Highfield were Walter Allen and John Hampson, who formed a link to the separate group of novelists and short story writers known as the Birmingham Group, which formed in 1935 after the American critic Edward O'Brien announced of "a new group of writers emerging in the Midlands, chiefly in and near Birmingham".

Well, surprise! Up pops Edward O’Brien, who edited 50 Best American Short Stories 1915-1939. O’Brien evidently got around.

The most authentically working class of the Birmingham Group authors was Leslie Halward, who was born over a butchers shop in Selly Oak and worked as a plasterer and toolmaker. Halward's major works were his short stories, collected in the two anthologies To Tea on Sundays and The Money's Alright and Other Stories, which captured an ambience "peculiarly appropriate to Birmingham" and were commended by E. M. Forster for their "good humour, the sureness and lightness of touch, the absence of any social moral.” In contrast to Halward's origins Peter Chamberlain was the grandson of Birmingham architect J. H. Chamberlain and of the city's first Lord Mayor James Smith. He was born in Edgbaston and educated at the private Clifton College. A notable motorcycle journalist and writer of short stories for the New Statesman, his novel Sing Holiday is a tale of motor racing set in Birmingham and the Isle of Man.

The Birmingham Group itself has a short Wikipedia entry. Here it is, in full:

The Birmingham Group was a group of authors writing from the 1930s to the 1950s in and around Birmingham, England. Members included John Hampson, Walter Allen, Peter Chamberlain, Leslie Halward and Walter Brierley.

Part of Birmingham's vibrant literary and artistic scene in the 1930s that also included the poets W. H. Auden, Louis MacNeice and Henry Reed; novelist Henry Green, the sculptor Gordon Herickx and the Birmingham Surrealists; the Birmingham Group shared little stylistic unity, but had a common interest in the realistic portrayal of working class scenes.

The group was christened by the American critic Edward J. O'Brien, who published several of their short stories in journals he edited and assumed they all knew each other. This became self-fulfilling, and for a while the group met weekly in a pub off Corporation Street.

Although the Birmingham Group are often described as working class novelists, they in fact had the varied social backgrounds that characterised Birmingham's distinctive high level of social mobility. The Birmingham-based poet Louis MacNeice described how

At this time, 1936, literary London was just beginning to recognise something

called the Birmingham School of novelists. Literary London, hungry for proletarian literature, assumed that the Birmingham novelists were proletarian. Birmingham

denied this. It could be conceded however that they wrote about the People with a knowledge available to very few Londoners.

— Louis MacNeice, The Strings are False: An Unfinished Autobiography

Armed with all that information, I again searched the internet for a portrait of Peter Chamberlain. Still no luck. However, I did find this, from As I Walked down New Grub Street: Memories of a Writing Life by Walter Allen:

Sometime in 1934 John [Hampson] and I were often joined in our Thursday meetings at the pub in Martineau Street which we visited every week by two other young writers, Peter Chamberlain and Leslie Halward, who were both some four or five years younger than John and some four or five years older than I. The man who brought us together was E. J. O'Brien, who edited an annual volume called The Best Short Stories of 19- and was the chairman of the editorial board of a newly founded little magazine called English Story for which we all wrote. Finding the four of us from Birmingham in his magazine, Edward had invented something he called the Birmingham Group and he added to our number by including in it two young men from Derbyshire, Walter Brierley and Hedley Carter.

Chamberlain came of a wealthy Birmingham family of bedstead manufacturers. He had been to school at Clifton and on our first meeting seemed to me very much the public school man, by which I mean that I found him arrogant. He was a large man, tall and broad, who looked as though he would have become fat and flabby in later years. I did not think we could have very much in common, he was so

obviously a man of a quite different world. He knew London at least as well as he did Birmingham and he had his own circle there. He knew writers: he had met Anthony Powell and told me of the cocktail party Powell had given for the people he had, unknown to them, put in his novels. Peter's literary heroes were the Americans, Hemingway and Fitzgerald especially, and it was from him that I first heard of John O'Hara. He lent me Appointment in Samarra and The Doctor's Son. He was, I thought, a bit smug. He had written a very short, astonishingly fresh story called “What the Sweet Hell”. It was published in the New Statesman, and on the Monday after publication a postcard arrived there saying the story was the most original thing the writer of the postcard had read for several years. The writer of the postcard was I. A. Richards. I think now that Peter had good reason to be smug. I remember too, that when his first novel, Sing Holiday, was accepted by Chatto and Windus he said, with what seemed to me maddening complacency, 'Well, you can't do better than the best, can you?'

He suffered from narcolepsy. In the simplest terms he could not control his sleep. I was with him in Regent Street one evening when he went to sleep walking and walked into a lamp standard. That woke him up. We went into the Cafe Royal. He put his arms on the table and his head on them and slept. It was my task to persuade the waiter that he wasn't drunk and hadn't passed out but that sleep was simply not in his control.

Before I met him he had been a racing motor cyclist. His condition had forced him to give that up. His ambition, if there was a war, was to join the Army as a motor cycling instructor, which carried with it the rank of sergeant, and remarkably enough, when war broke out he did exactly that. His disease was unspotted at the medical examination, and he successfully hid it throughout the war.

So much for a picture being better than a thousand words.

Allen’s portrait of Chamberlain was so clear and sharp that I went and ordered As I Walked down New Grub Street from ABE Books.

According to Trials Guru website:

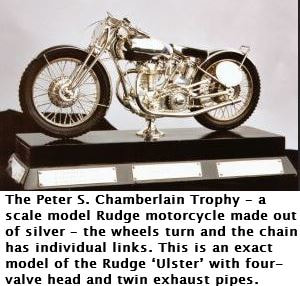

During the war years, [Bob] MacGregor [a greengrocer from the Perthshire village of Killin who was a factory supported rider for Rudge] and his trials riding comrades were enlisted and many became Army dispatch riders and motorcycle instructors. Their off-road riding skills being put to very effective use by the British military. The Rudge factory directors were so enamoured by MacGregor’s achievements in the Scottish that they presented a trophy named the Peter S. Chamberlain Trophy, which was a scale model Rudge racing motorcycle made in silver, to the Edinburgh club and for many years it was used as a best first time rider award, until the cost of insurance resulted in the club retiring the award to safe keeping, such was it’s value.

Trials Guru does not note that Chamberlain too was one of the motorcycle instructors whose skills were put to use in the war.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed