Hmmm... Talk about pompous.

By “aesthetic experience” I mean the sum total of one’s reactions, emotional and rational, to an artwork – a piece of music, a poem, a passage in a book – with all their accompanying biases and loyalties, theories and opinions, standards of beauty and of ugliness, and appeal to personal taste.

There are two or three musical guess-who’s – who’s the composer? – I’m putting together for another post.

Today’s guess-who game:

Here are passages from a novella by which Russian?

He wore a wig, moustaches, whiskers, and even a little 'imperial'—all, every hair of it, false, and of a magnificent black colour; he rouged and powdered every day. It was said that he had little springs to smooth away the wrinkles on his face, and these springs were in some peculiar way concealed in his hair.

It would never occur to anyone looking at her that this majestic lady was the greatest gossip in the world, or at any rate in Mordasov. One would suppose, on the contrary, that gossip would die away in her presence, that backbiters would blush and tremble like schoolboys confronting their teacher, and that the conversation would not deal with any but the loftiest subjects. She knows about some of the Mordasov people facts so scandalous and so important that if she were to tell them on a suitable occasion and to make them public, as she so well knows how to do, there would be a regular earthquake of Lisbon in Mordasov.

The colonel's wife, Sofya Petrovna Karpuhin, had only a moral resemblance to a magpie. Physically she was more like a sparrow. She was a little lady, about fifty, with sharp little eyes, with freckles and yellow patches all over her face. On her little dried-up body, perched on strong, thin, sparrow-like little legs, was a dark silk dress which was always rustling, for the colonel's lady could not keep still for two seconds.

Have you made a guess?

The passages are from novella, Uncle’s Dream, by Фёдор Михайлович Достоевский (translated by Констанц Гарнэтт).

Uncle’s Dream – From the Annals of Mordasov is farce.

My bet is that Достоевский first conceived it as a theater piece. Except for a short carriage ride, and a lachrymose scene that takes place in a poorly lit hovel, the plot unfolds in four interiors in three homes of members of the landowning class in provincial Russia in the second half of the 19th century. Imagine what fun the sentimental authenticity-obsessed BBC property crew would have with Masterpiece Theater’s Uncle’s Dream (possibly retitled Annals of Mordasov): Samovar Victorian.

When Uncle’s Dream is farcical, which is most of the time, it ranges from the amusing to the hilarious – just as a farce should. Sometimes Достоевский, the novelist, takes over and, for a page or so, we are entertained with ideas – analogies, metaphors, ruminations philosophical, psychological or historical, etc. – which could not be conveyed on the stage.

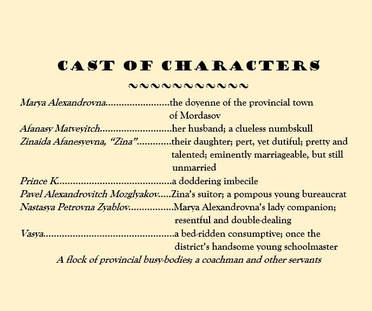

The plot revolves around the efforts of Marya Alexandrovna to marry off her daughter, Zina, to the decrepit, imbecilic Prince K.

Marya Alexandrovna is the protagonist of Uncle’s Dream. The BBC production would be a tour de force for one of those character actresses who find their true stride in middle age. Personally, I’d love to see Marya Alexandrovna, a wily, subtle, vivacious firebrand, played by Helena Bonham Carter in her 50-year-old reincarnation – a coloratura who has matured into a mezzo.

Elaborating my theory that Uncle’s Dream was originally conceived for the stage, I propose that it became a novella when Marya Alexandrovna became so intriguing to Достоевский that he could not forego the delight of developing her character.

Достоевский, in the character of the narrator, puts it this way:

I may as well confess betimes I have rather a partiality for Marya Alexandrovna. I wanted to write something like a eulogy on that magnificent lady, and to put it in the shape of a playful letter to a friend, on the model of the letters which used, at one time, in the old golden days that, thank God, will never return, to be published in the Northern Bee and other periodicals. But as I have no friend, and have, moreover, a certain innate literary timidity, my work has remained in my table drawer.

Unfortunately, the same neither-fish-nor-fowl fuzziness that destroyed the film, The Death of Stalin, nearly ruins Uncle’s Dream.

[SPOILER ALERT]

True to the protocols of farce, Zina’ engagement to Prince K – which Marya Alexandrovna had wheedled out of him after getting him drunk – is on-again-off-again. After Zina calls it off once again – at the end of Act II, or in Episode 10 of the 12-episode Masterpiece Theater series – she pays a visit to the dying Vasya who, as has been obvious all along, is Zina’s true love.

Suddenly, in the midst of this charming provincial farce, Достоевский plunges us into a squalid deathbed scene, complete with grieving mother.

His old mother, who had been for a whole year, almost to the last hour, hoping for her Vasya's recovery, saw at last that he was not long for this world. She stood over him now crushed with grief, but tearless, clasping her hands and gazing at him as though she could never look at him enough; and though she knew it, she could not grasp that in a few days her Yasya, the apple of her eye, would be covered by the frozen earth out yonder under the snowdrifts in the wretched graveyard. But Vasya was not looking at her at that moment. His whole face, wasted and marked by suffering, was full of bliss. He saw before him, at last, her of whom he had been dreaming, asleep and awake, for the last year and a half in the long, dreary nights of his sickness...

"Zina," he said, "Zinotchka! Don't weep over me, don't mourn, don't grieve, don't remind me that I shall soon die. I shall look at you—yes, as I am looking at you now- I shall feel that our souls are together again, that you have forgiven me; I shall kiss your hands again as in old days, and die, perhaps, without noticing death! You have grown thin, Zinotchka! My angel, with what kindness you are looking at me now. And do you remember how you used to laugh in old days? Do you remember?”

Vasya continues in this vein for four more pages.

The reader wonders – at least, this reader did – where is Достоевский going with this? Will Vasya suddenly sit up, hale and hardy, and confess he’s been faking? Will there be a deathbed marriage officiated by a priest who’s come to administer last rites, after which it is discovered that Vasya was Prince K’s son, so that Zina, as Vasya’s widow, inherits all that she would have acquired if she had married the Prince – who fortuitously has just died in a fit of apoplexy in the drawing room of Sofya Petrovna Karpuhin, Marya Alexandrovna’s sworn enemy? Will Mozglyakov, who has followed Zina to Vasya’s hovel, shocked into an act of Christian charity by the pathos he encounters there, offer to take Vasya into his own home and nurse him to health, thus winning Zina’s heart?

No such luck. Vasya just dies. That’s it.

Up to the very last moment he gazed at Zina, still sought her with his eyes, and when the light in his eyes was beginning to grow dim, he still, with a straying, uncertain hand, felt for her hand to press it in his. Meanwhile the short winter day was passing. And when the last farewell gleam of sunshine gilded the solitary frozen window of the little room, the soul of the sufferer parted from his exhausted body and floated after that last ray.

Evidently, Vasya’s only purpose in life – and this is all there is of Vasya’s life, one scene in an obscure Достоевский novella – seems to have been to allow Достоевский to indulge in one of those embarrassingly maudlin scenes which are the bane of his novels. Or perhaps Vasya’s purpose in life was to permit Vladimir Nabokov to indulge in that impish exercise in criticism which caused as much consternation in some circles as his seemingly sympathetic treatment of a pedophile did in others.

Достоевский is not a great writer, but a rather mediocre one... [Some readers] do not know the difference between real literature and pseudoliterature, and to such readers may Достоевский seem more important and more artistic than such trash as our American historical novels or things called ''From Here to Eternity'' and suchlike balderdash.

Following Vasya’s melodramatic demise, the comedy of Uncle’s Dream resumes, but the effect is as if, with the curtain drawn between Acts II and III of a farce about provincial social climbing, we were treated to a musical interlude of a particularly lugubrious performance of the slow movement from a Bruckner symphony.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed