I’ve had my Routledge & Kegan Paul paperback, 1980, on my shelf for years (probably picked it up used somewhere), and finally took it down to read. I was toodling merrily along – Meyers forges ahead at just the right speed, not slacking as he takes you through Lewis’ (mainly miserable) life, but not so posthaste that he can’t point out the interesting scenery – when, all of a sudden, I encountered two blank pages. Twelve pages of the book turned out to be blank – six facing pairs.

Kindle didn’t have Enemy, nor did I-Books. It was listed on ABE Books (I’m currently boycotting Amazon, as well as Israel), but I was impatient. Fortunately, there was one copy in the vast Mid-Hudson Library System – in Woodstock, naturally. (Naturally, not because of Woodstock’s current incarnation as a 1960’s theme park, but because of its earlier existence as an artist’s colony.) In a couple of days I was able to pick it up in my local library.

As I say, the scenery around Lewis’ life is interesting, and I’ve been constantly interrupting my reading to go to my I-Pad to track down some reference, a painter or writer (or painting or book) I hadn’t heard of, or had only vaguely heard of, or a picturesque dipsomaniac hanger-on who manages to find his way to the best parties, or a sexy bluestocking with “Lady” before her name.

A painter named Mark Gertler briefly appears in Lewis’ life. Gertler was the fervidly frustrated unrequited wooer (except for a single quickie, some websites suggest) of Dora Carrington. He’s a character in the movie, Carrington, which to this old and over stimulated mind has become only vaguely memorable.

Wikipedia has an article on Gertler, if you’re curious – as I was. It includes a lengthy sketch of him by Virginia Woolf, which I’ll quote in full, because it’s amusing and, who knows, it might disappear from Wikipedia tomorrow.

“Good God, what an egoist!” We have been talking about Gertler to Gertler for some 30 hours; it is like putting a microscope to your eye. One molehill is wonderfully clear; the surrounding world ceases to exist. But he is a forcible young man; if limited, able & respectable within those limits; as hard as a cricket ball; & as tightly rounded & stuffed in at the edges. We discussed — well, it always came back to Gertler. “I have a very peculiar character ... I am not like any other artist ... My picture would not have those blank spaces ... I don’t see that, because in my case I have a sense which other people don’t have ... I saw in a moment what she had never dreamt of seeing ...” & so on. And if you do slip a little away, he watches very jealously, from his own point of view, & somehow tricks you back again. He hoards an insatiable vanity. I suspect the truth to be that he is very anxious for the good opinion of people like ourselves, & would immensely like to be thought well of by Duncan [Grant], Vanessa [Bell] & Roger [Fry]. His triumphs have been too cheap so far. However this is honestly outspoken, & as I say, he has power & intelligence, & will, one sees, paint good interesting pictures, though some rupture of the brain would have to take place before he could be a painter.

So there were people like that back in 1918. I thought it was a 21st century malady. (There was an earlier version of the disease, based more on status than ego, a symptom of which can be detected in the sentence that begins, “I suspect the truth to be that he is very anxious.”)

(The Wikipedia article ends with a note that Gertler’s home is now the “atelier” of some tailor “who has, according to Vogue, ‘dressed some of the world's most famous people.’” The Wikipedia article about the tailor is longer than the article about Gertler, although – from Woolf’s account of him – if he were alive now, Gertler would have made damn sure that was not the case.)

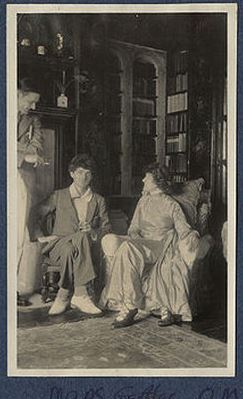

Gertler and his "patron," Lady Ottoline Morrell. The fellow standing on the left, half-in, half-out, is a poet by the name of Eliot or some such thing.

When I had been able to read the Oxford entry for Gertler, I came across a reference to a writer I had never heard of, Greville Texidor. Just the name was intriguing. The connection with Gertler was that a character in a novella of Texidor’s, These Dark Glasses, was said to be based on Gertler. Texidor had met Gertler, and the connection between Gertler and the painter in Texidor’s novella is that they do not work outdoors, only in their studios. But Gertler was forbidden by doctors from painting outdoors when the tuberculosis that killed him was in its final stages; Texidor’s painter (a secondary character) works strictly indoors because he is an anti-social, contrary boor.

There is no Wikipedia article on Greville Texidor. The most informative piece is on a moderate anarchist website, libcom.org, which pairs Texidor – who, I was surprised to discover, was a woman – with her anarcho-syndicalist lover, Werner Droescher.

Texidor had quite a life. Here are excerpts from the libcom.org article (which, with insouciant political incorrectness, usually refers to Texidor as “Greville” and to Droescher mostly as “Droescher”):

Greville Texidor was born in 1902 at Wolverhampton... Her father, a barrister, committed suicide in 1920 due to a scandal [?]. Her mother was an artist who had originally moved from Auckland in New Zealand to study art in London in 1895.

Greville grew up around many famous artists and writers including DH Lawrence, Mark Gertler, Stanley Spencer, and Augustus John who used her as a painting model...

She joined a Bluebell Girls chorus line... and travelled around the world. At one point she travelled with a German who did a contortionist act.

... She danced at the New York Winter Garden for 2 years... [In 1929, in] Buenos Aires she married the person she referred to as the "Spaniard”, Manuel Maria Texidor i Catasus...

The family moved... to the village of Tossa de Mar on the Costa Brava in 1933... A small colony of painters and writers began to settle there. The painter Marc Chagall named Tossa the “Blue Paradise”. Here Greville met Werner Droescher and had a passionate affair with him.

...In 1935 Greville separated from Manuel.

...With the outbreak of the Revolution Werner enlisted with a POUM column [in Barcelona].

Greville had meanwhile enrolled in the militia, and had joined Werner after tremendous difficulties. They became part of one of the Anarchist Centurias in La Zaida after the other members of the original POUM group left... With other centurias they engaged in military action and constructed defensive trenches. In the evenings they tried to persuade the peasants of the village to form an agricultural collective.

Here Emma Goldman visited them...

They took part in the invasion of Almudeva in August 1936...

[The couple went to England to propagandize for Help for Spain committees, returned to Spain, worked there with a Quaker refugee relief agency, then with a Paris-based Communist refugee organization, which fired them because it did not approve of their politics. After Spain fell to Franco, Texidor returned to England]

With the outbreak of the World War Droescher... was interned at Seaton in Devon. Texidor... as a consequence of marrying a German... was interned in Holloway prison.

Greville’s mother, with the help of Augustus John, got them released and they were allowed to move to New Zealand.

Droescher and Texidor became friendly with... members of the North Shore intelligentsia [?]... Texidor wrote a series of short stories, which were eventually published in 1987 (long after her death) by Victoria University Press. She also translated Spanish literature into English, including poetry by Garcia Lorca. When the poet and obnoxious drunk Dennis Glover, part of the North Shore group, began to taunt her about the triumph of Franco, Texidor took a steak knife and held it to his throat until bystanders could overpower her.

...In 1948 [they moved] to Australia.

...In the sixties [Texidor and Droescher] separated. Greville moved back to Spain and spent the last years of her life in Europe, moving to Australia shortly before her death in 1964 [by suicide, according to another website.]

Naturally, I wanted to read These Dark Glasses which, despite what the libcom.org entry says, was published while she was alive, in 1949 in New Zealand. That edition is unavailable, but I found the novella in Google Books – included in the collection published in 1987 which has the Carveresque (Lishian, rather) title, In Fifteen Minutes You Can Say a Lot.

So, once again, I began to read – not merrily along, this time, but intensely absorbed, as one is with a really good story. And really good it is. It has its own unique style, sort of flat and seemingly emotionless. But These Dark Glasses is written in the form of diary entries of a young woman who is renting a room on the Côte d’Azure, taking a break from fighting in the Spanish Civil War (on the Republican side, of course), in which her lover has recently been killed. Thus the style is an element of the story, an expression of the narrator’s state of mind, and its flatness, which recounts every event, from the trivial to the momentous, in the same matter-of-fact tone, is a reflection of deep emotions. The style also – as you can imagine (the trivial and momentous being given the same weight) – fizzes with irony, like Stendhal’s.

“If the other stories are as good as this,” I thought to myself, “I’m going to recommend it to New York Review Books as a candidate for reprint.” Then – horrors! – the Google Book text ended before the story did.

I found a copy on ABE Books and am now awaiting its arrival – from New Zealand.

Well, no problem, one would think. Back to Google Images, where I have found so much of the artwork mentioned in the book. Alas, among all the zillions of images on the internet, from the recondite to the iconic to the pop-glazed to the pure crap, Wyndham Lewis’ portrait of Eleanor Martin (or Mrs. Paul Martin – I checked) is not included. Typical of Lewis’ luck.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed