Rebecca West

Rebecca West The book is Turnstile One, a “Literary Miscellany from The New Statesman and Nation,” edited by V. S. Pritchett, published in 1948 by The Turnstile Press.

There is poetry (E. M. Forster, Arthur Waley, Auden, C. Day Lewis, MacNeice, Spender, Roy Campbell, de la Mare, Betjeman, Victoria Sackville West, et. al.), short stories (H. G. Wells, H. E. Bates, Elizabeth Bowen, composer Ethyl Smythe, two Stracheys – John and Julia – et. al.), and essays and reviews (Rebecca West on Kipling, James Joyce on opera, Cyril Connolly on Noel Coward, D. H. Lawrence on the Germany and the Germans of 1928, Harold Laski on booksellers, Forster on prigs, Belloc with a Shandyish five-and-a-half pages entitled, “On I Know Not What”, Stevie Smith on the summer exhibit at the Royal Academy (1938), two Woolfs – Leonard on Jane Austen and Virginia on Sir Walter Scott – et. al.).

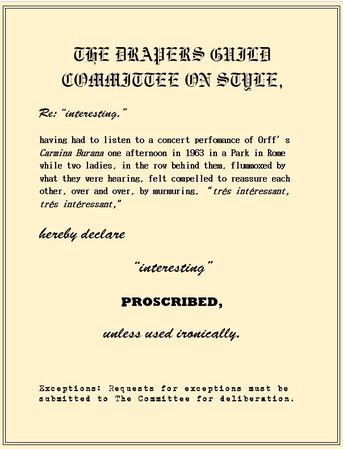

And, oh boy, it is interesting.

What is most interesting is that authors whose view of the world and the human condition I had assumed to have been broad and clear enough for them to have been skeptical about any ideology, in these occasional pieces for a left-wing – essentially Fabian – weekly, reveal surprisingly narrow views, all tinted pink.

That is especially interesting in that it proves that the political fallacy which mars so much writing today – from academia to The New Yorker - is not a unique phenomenon. Just as identity politics infects today’s writers, right down to their use of pronouns, back in the 20’s and 30’s writers who were considered serious and intelligent arbiters of art and culture, when certain subjects came up felt compelled to write their own sort of well-reasoned trash, arguing for one rigid socialist ideology or another.

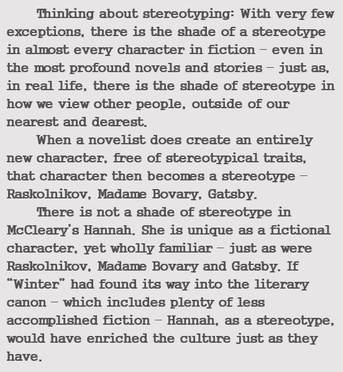

§ A disapproving essay/obituary on Kipling by Rebecca West (1936)

Understandably, it is much easier for us to get past Kipling’s racist, jingoistic imperialism and into his sympathetic, humanist heart, than it was for left-wingers of the 1930’s. West, author of the masterpiece, Black Lamb and Grey Falcon, has a hard time finding anything nice to say about Kipling’s writing, and when she does, it is modified by a “but.”

Ultimately, West judges Kipling not on his art, but on his politics.

You can’t really accuse West of succumbing to the political fallacy here, though. Kipling was not just another writer whose politics were distasteful to the following generation of writers, literati and intellectuals. A good deal of Kipling’s work is political commentary; he even used his renown to become a political operative by, for example, intervening – for the Conservatives – in the 1911 Canadian election. Kipling’s political positions were part of his public persona, so it’s perfectly appropriate for West to damn Kipling on political grounds.

Here is West's penultimate paragraph on Kipling:

But the same wonder regarding the value of our English system of education arises when we look round at Kipling's admirers among the rich and great. He was their literary fetish; they treated him as the classic writer of our time; as an oracle of wisdom; as Shakespeare touched with grace and elevated to a kind of mezzanine rank just below the Archbishop of Canterbury. But he was nothing of the sort. He interpreted the mind of an age. He was a sweet singer to the last. He could bring home the colours and savours of many distant places. He liked the workmanship of many kinds of workers, and could love them as long as they kept their noses to their work. He honoured courage and steadfastness as they must be honoured. But he was not a faultless writer. His style was marred by a recurrent liability to a kind of two-fold vulgarity, a rolling over-emphasis on the more obviously picturesque elements of a situation, whether material or spiritual, and an immediate betrayal of the satisfaction felt in making that emphasis. It is not a vice that is peculiar to him—perhaps the supreme example of it is Mr. Chesterton's Lepanto—but he committed it often and grossly. Furthermore, his fiction and his verse were tainted by a moral fault which one recognizes most painfully when one sees it copied in French books which are written under his influence, such as M. de St Exupéry's Vol de Nuit, with its strong, silent, self-gratulatory airmen, since the French are usually an honest people. He habitually claimed that any member of the governing classes who does his work adequately was to be regarded as a martyr who sacrificed himself for the sake of the people; whereas an administrator who fulfils his duties creditably does it for exactly, the same reason that a musician gives a masterly performance on his fiddle or a house-painter gives a wall a good coat of varnish, because it is his job and he enjoys doing things well. But the worst of all was the mood of black exasperation in which Kipling thought and wrote during his later years He had before him a people who had passed the test he had named in his youth—the test of war, and they had passed it with a courage that transcended anything he can have expected as far as war transcended in awfulness anything he can have expected. Yet they had only to stretch out a hand towards bread or peace or power or any of the goods that none could grudge them in this hour when all their governors' plans had broken down, for Kipling to break out in ravings against the greed and impudence of the age. Was this a tragedy to deplore or a pattern to copy?

One more interesting tidbit from West’s essay. Her very last sentence:

It has often seemed fantastic that the author of “MacAndrew's [sic] Hymn” should have feared and loathed the aeroplane. (“McAndrew’s Hymn”, one of Kipling’s wry-ruffian monologues, celebrates the steamship.) Perhaps he felt that, had he given his passion for machinery its head, that and the rest of his creed might have led him straight to Dnieprostroi.

I knew what Dnieprostroi referred to only because I recently had read Yuri Slezkine’s The House of Communism – even then, I had to check. Dnieprostroi was a huge hydroelectric dam, still under construction when West was writing, that was proving to the world that the Soviet Union was capable, sans capitalism, of a massive and technologically complex public works project. What is interesting is that in 1936 West assumed that most of The New Statesman and Nation’s readers would understand the reference.

(TO BE CONTINUED)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed