Then my eye caught this:

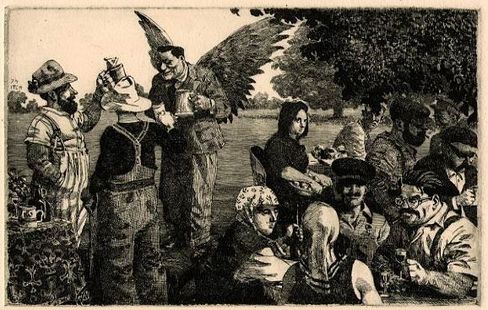

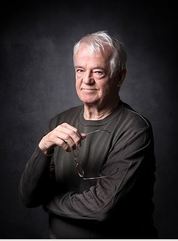

Itchkawich was pleased that I liked his stuff, although like many visual artists, he did not have much to say about it. On a gallery website, he is quoted thus: "My work represents invented situations which look believable at first glance. I feel it is almost a test to see whether I can create a believable, interesting situation with a good composition.” That succinctly sums up his work.

I didn’t buy an Itchkawich that day. I’m not sure why. The prices may have been a little too rich for me. I later bought a book, When Men Were Animals and Animals Were Men: A Study of the Graphic Work of David Itchkawich by John R. Mattingly, with eighteen Itchkawich etchings, published in 1976.

Mattingly’s admiring critique of Itchkawich in When Men Were Animals is one of the most pretentious things I have ever read. Mattingly’s pretentiousness is so naive that one feels for him, as one feels for a hopelessly naive character in a work of fiction. (Prince Mishkin comes to mind.)

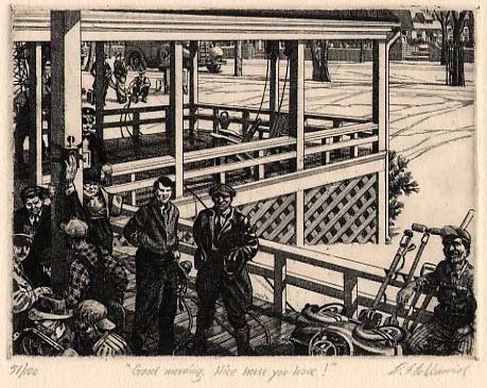

For example, in his notes on the etching, “The Hearing” Mattingly says, “Though the etching is called ‘The Hearing’, there appears nothing to hear. Why was it not called ‘The Waiting’ or ‘Attendance at Court’?” Mattingly’s cluelessness takes flight in the paragraph before that: “Though four of the participants are standing, there is no explanation of why they are standing. They appear to be tired rather than deferential. And if it were respect that they show, it would have to be for a series of banisters set on top of a partition so high that it would be barely possible to see through them.”

Like an unreliable narrator, whose skewed sensibilities are a poignant lens through which we can more deeply experience a work of fiction, Mattingly is an unreliable critic, whose skewed sensibilities are a poignant lens through which we can more deeply experience the art of David Itchkawich.

I assumed that, in his clueless way, Mattingly was missing some significance in the name Martin Schwab. I assumed, in my own clueless way, that Martin Schwab was a figure in the political landscape of early 20th century Eastern Europe – someone Mattingly could have looked up in a library, if he could have spared a moment from his alloted task of scattering seeds of Levi-Strauss throughout the plains of Western philosophy.

Wrong. Pre-Google, Mattingly would have had a hard time discovering the identity of Itchkawich’s Martin Schwab. (He could have asked Itchkawich, of course; but consulting the artist is something no respectable art critic can be expected to do.) It turns out that Martin Schwab was a fairly obscure German movie actor. (Fairly obscure = just a short entry in German Wikipedia.)

There is no question that, among Google’s many Martin Schwabs, this one is Itchkawich’s dedicatee.

The meaning of Itchkawich’s etchings (like the meaning of any successful artwork) is more than language is capable of expressing. Even whatever meanings Itchkawich, himself, might come up with would be only be fragmentary – one layer of innumerable layers of meaning that can be drawn from the same-old.

There’s nothing wrong with the same-old. It is the same-old same-old that is a bore. The same-old is what makes a created work – a poem, a piece of music, a painting, an embroidered handkerchief – a work of art. To unconscionably generalize: the same-old for the Greeks was myth; then the Romans added history; these were cast aside for a millennium, during which the same-old was the worship of Jesus; when that worship began to be regarded as nothing more than that old workhorse, myth, the human condition, primarily that of love, joined myth and history in the magnificent same-old of the 19th century; then came the modern age, and the elevation of style to the rank of same-old. In that sense, Itchkawich’s same-old is the same-old of Bosch, of Piranesi, of Fuseli, of Ensor.

Somewhere in his book Mattingly protests that Itchkawich is not Kafkaesque. Of course, Itchkawich is Kafkaesque. Kafka has become part of The Great Same-Old on High, which we know as our culture.

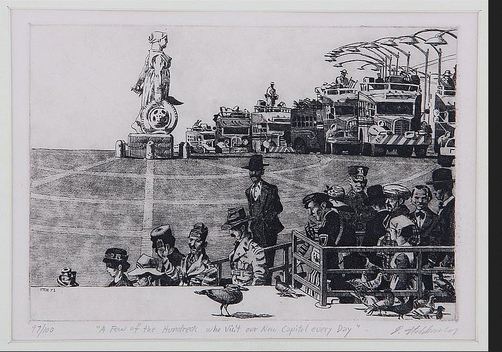

That is Itchkawich’s real medium: our culture (his and mine; I don’t know if its yours if you’re under forty). His palette is a profusion of cultural references, which he combines in subtle ways. For example, the array of headgear in “A Few of the Hundreds” evokes a specific, yet imaginary, cultural moment, like a bank of flowers in a Monet might evoke a specific, yet imaginary, hour in a specific season.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed