I have tried to avoid using the word “interesting” ever since, after a performance of Orff’s Carmina Burana in a park in Rome in 1962, two French women of a certain age, sitting nearby, nonplussed by what they’d just heard, kept nodding sagely to each other and repeating “très intéressant, très intéressant,” but no other word seems to do in this case.

The book, an anthology published by Doubleday, An American Omnibus, dated 1933, which I must have picked up in a used bookstore and has been sitting on my shelves for years, engaged my interest on many fronts.

In an introduction, Carl Van Doren coyly – mentioning no names – explains its origins:

The Omnibus came out of an argument. Perhaps it was less an argument than a game. Three or four critics were matching favorites. Do you remember this? How about that? What else is as good as so and so? Nobody was being solemn and systematic. Everybody was naming what he particularly liked... They made notes and talked them over with a publisher.

First of all, the book, the physical book, is interesting in itself. It is printed in many different typefaces. Van Doren explains: “If the volume was to be large, and yet not too expensive, it must be printed from plates already cast – one book made up of the parts of many books.” One section is entitled “Selections from ‘The New Yorker’”, with fourteen pieces that have the feel of “Talk of the Town” items. Sure enough, there’s The New Yorker’s distinctive title font and bold, clear typeface.

And I think you’ll agree that the table of contents is interesting:

RING AROUND A ROSY Sinclair Lewis

THE KILLERS Ernest Hemingway

ARCHY AND MEHITABEL Don Marquis

BIG BLONDE Dorothy Parker

THE NEW FABLE OF SUSAN AND THE DAUGHTER AND THE GRAND

DAUGHTER AND THEN SOMETHING REALLY GRAND George Ade

BUT THE ONE ON THE RIGHT Dorothy Parker

THIRTY-SEVEN Patricia Collinge

COME, YE DISCONSOLATE Charles MacArthur

BUT FOR THE GRACE OF GOD Thyra Samter Winslow

THE VANDERBILT CONVENTION Frank Sullivan

MARRIAGE OF CONVENIENCE John Mosher

THE STRANGER Emily Hahn

THE GIANT-KILLER T. H. Wenning

THE TITLE Arthur Kober

LOUIS DOT DOPE Robert Benchley

MISS GULP Nunnally Johnson

MY SILVER DRESS Elinor Wylie

THE FAITHFUL WIFE Morley Callaghan

ESSAYAGE Christopher Morley

CHAMPION Ring Lardner

DEATH IN THE WOODS Sherwood Anderson

MARY OF SCOTLAND (A Play) Maxwell Anderson

PAPAGO WEDDING Mary Austin

THE KILLER Stewart Edward White

SELECTION FROM "PERSONAL HISTORY” Vincent Sheean

Then there are poems by Edwin Arlington Robinson, Robert Frost, Carl Sandburg, Sara Teasdale, John Gould Fletcher, H. D., William Rose Benét, Robinson Jeffers, Elinor Wylie, T. S. Eliot, John Crowe Ransom, Conrad Aiken, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Archibald MacLeish, Phelps Putnam, E. E. Cummings [sic], Louise Bogan, Stephen Vincent Benét, Léonie Adams, Allen Tate, and Hart Crane.

The table of contents does not list page numbers because, since the original plates were used, the pages retain their original numbering. (Lardner’s Champion ends on a page numbered 127; the Sherwood Anderson story which immediately follows it begins on a page numbered 407. The pages of “Selections from The New Yorker” are numbered 1-63. The original New Yorker lithography would have been sized to the magazine’s narrow columns, so the magazine must have re-set these pieces for this anthology.)

The Omnibus is oddly top-heavy. Of its 820 pages, 196 are devoted to Archy and Mehitabel, 202 to Maxwell Anderson’s play and 134 to Stewart Edward White’s The Killer. (Hemingway’s The Killers takes all of nine pages.) The poems are on the final 46 pages.

Although I say I finished An American Omnibus, that doesn’t mean that I read the whole thing. In fact, I only read about half of it, skipping the two 200-page opuses, Maxwell Anderson’s play and Archy and Mehitabel, and a few other things.

I read Sinclair Lewis’ Ring around a Rosy right to the end simply because it was the first story in the book. If I’d known at that point that I would be allowing myself to skip what I didn’t like, I would have stopped when I realized, as I soon did, that Ring around a Rosy was an artless polemical exercise. I gave up on Ring Lardner’s The Champion after a couple of pages. It was clear that the point of the story was its ending, and I knew from the start what that would be – as I also did with the Sinclair Lewis story.

The New Yorker selections are a mixed bag. There is a dull piece by Dorothy Parker about being seated next to a bore at a dinner party, which is only slightly redeemed by the revelation that Victorian dinner party conventions were scrappily struggling on in flapper New York. Parker’s stand-alone story, Big Blonde, however, is one of the best things in the book. Many of the other New Yorker pieces also are too frothy, considering that the brew beneath the froth is long gone. The Robert Benchley contribution is disappointing. Louis Dot Dope purports to be an description by Benchley, in the guise of a crass American just returned from abroad, of the court of Louis XVI.

There is a typical New Yorker profile – arch and cocky and full of juicy facts – by Charles MacArthur, Come Ye Disconsolate, about Frank E. Campbell who, if you were in New York in the 1950’s and 1960’s, as I was, you assumed had a monopoly on funeral parlors in Manhattan. The funniest piece – worthy of the best of today’s “Shouts and Murmurs” – is Frank Sullivan’s attempt to unravel the complexities of the populous Vanderbilt family. (“Now then. The Cornelius Vanderbilt who married Alice Gwynne was not the Cornelius whose yacht recently blew up in the East River. No. The Cornelius whose yacht blew up in the East River is the Cornelius who married Grace Wilson.”)

~

Maxwell Anderson’s Mary of Scotland is a pretentious yawn (at least it seems so at this remove). I skimmed through it, to see if it might improve, but it didn’t. In notes on the authors, at the end of An American Omnibus, Mary of Scotland is credited with having won the 1934 Pulitzer Prize – wishful thinking on someone’s part. The 1934 Pulitzer Prize for Drama was won by Sidney Kingsley’s Men in White. Anderson did win the 1933 Drama Pulitzer – for a sort of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington called Both Your Houses.

My guess is that Mary of Scotland fails because Anderson was overawed by the subject matter and by the overshadowing reputation of Schiller’s canonic and lugubrious Mary Stuart. Anderson’s aim is to use modern speech patterns to throw open the windows on this stodgy old story, but he can’t completely discard the antiquarian tenor which the 19th century brought to it.

From Anderson’s play:

ELIZABETH

Yes, yes – and it’s well sometimes

To be mad with love, and let the world burn down

In your own white flame. One reads this in romances –

Such a love smokes with incense; oh, and it’s grateful

In the nostrils of the gods!

From Schiller’s:

BURLEIGH (to ELIZABETH)

While in her castle sits at Fotheringay,

The Ate [goddess of mischief] of this everlasting war,

Who, with the torch of love, spreads flames around;

~

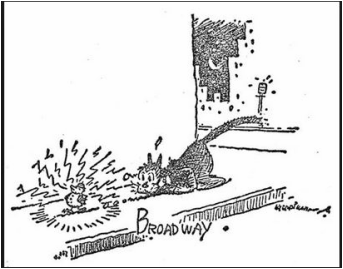

It has been many years since I last looked at Archy and Mehitabel. After an initial wave of nostalgia, my impression, revisiting Archy in the Omnibus in its familiar, original glory – illustrations and all – was exactly the same as it was when I was a pre-teen: amusing, but once you get the point, not worth reading from beginning to end. (Archy was first published as a serial in the Sun. I can imagine that in short, periodic bursts its cleverness might have overcome the fact that it really was just a one-trick pony. After all, daily comic strips do very well as one-trick ponies.)

a lightning bug got

in here the other night a

regular hick from

the real country he was

awful proud of himself you

city insects may think

you are some punkins

but i don t see any

of you flashing in the dark

like we do in

the country all right go

to it says i mehitabel the

cat and that green

spider who lives in your locker

and two or three cockroach

friends of mine and a

friendly rat all gathered

around him and urged him on

and he lightened and

lightened and lightened you

don t see anything like this

in town often he says go to it

we told him it s a

real treat to us and

we nicknamed him broadway

which pleased him

~

If it had not been written in 1919, one could accuse White of writing with an eye to Hollywood. Along with cowboys straight out of every Western you’ve ever seen, the characters include an odd-ball Easterner – a jockey who is a junkie, of all things – who proves his mettle at the end, a doughty damsel in distress, some nasty Mexicans, and a villain so evil that, if a bird calls or a frog croaks within earshot of his ranch house, he sends his men out to shoot it; and every scene is cinematically atmospheric.

He drove all hunched up. His buckboard was a rattletrap, old, insulting challenge to every little stone in the road; but there was nothing the matter with the horses or their harness. We never held much with grooming in Arizona, but these beasts shone like bronze.

or

The thin blue curl of smoke had caught my eye; and I became aware of the figure of a man seated on the ground, in the shadow, leaning against the building. The curl of smoke was from his cigarette. He was wrapped in a serape which blended well with the cool colour of shadow.

or

A reconnaissance disclosed a little battle going on down toward the water corrals. Two of our men, straying in that direction, had been fired upon. They had promptly gone down on their bellies and were shooting back.

“I think they’ve got down behind the water troughs,” one of these men told me as I crawled up alongside. “Cain’t see how many there is. They shore do spit fire considerable. I’m just cuttin’ loose where I see the flash.”

According to Teddy Roosevelt, Stewart Edward White was “the best man with both pistol and rifle who ever shot” at his Sagamore rifle range. Roosevelt might have added that White was a great writer too, but those were the days when every educated gent, even if not a good shooter, was assumed able to produce mellifluous prose.

White sets his story’s scene in a way he should not – at least, according to the show-don’t-tell strictures of creative writing classes – but this is delicious, I’m sure you’ll agree:

...this was in the year of 1897 and the Soda Springs valley in Arizona.

By these two facts you old timers will gather the setting of my tale. Indian days over; "nester" days with frame houses and vegetable patches not yet here. Still a few guns packed for business purposes; Mexican border handy; no railroad in to Tombstone yet; cattle rustlers lingering in the Galiuros; train hold-ups and homicide yet prevalent but frowned upon; favourite tipple whiskey toddy with sugar; but the old fortified ranches all gone; longhorns crowded out by shorthorn blaze-head Herefords or near-Herefords; some indignation against Alfred Henry Lewis's Wolfville as a base libel; and, also but, no gasoline wagons or pumps, no white collars, no tourists pervading the desert, and the Injins still wearing blankets and overalls at their reservations instead of bead work on the railway platforms when the Overland goes through. In other words, we were wild and wooly, but sincerely didn't know it.

Please note the and, also but. Not many writers are both careful and self-confident enough to write and, also but. For example, Henry James was a careful writer, but I do not think he would have had the guts to write “Mrs. Brookenham looked quickly around the room and, also but, she spoke with utter detachment.”

If you’re curious about Alfred Henry Lewis’s Wolfville, you can click here, but White’s problem with Wolfville is clear from this description of its style:

Pronouns include you-alls, we-alls, and they-alls. “Which” functions as an all purpose relative pronoun and can be found at the beginnings of sentences even as the first word of a story. Language is often figurative and mixed with unexpected analogies. A man is described as so obstinate that he “wouldn’t move camp for a prairie fire.” An action with no useful effect is said to be like “throwin’ water on a drowned rat.”

But there are greater depths to The Killer. White seems to channel Gogol – not the Gogol who shaded into the Kafkaesque in The Nose and The Overcoat, but the Gogol of the Cossack stories.

First of all, in the first paragraph, there is the Gogol who keeps testing the fourth wall.

I want to state right at the start that I am writing this story twenty years after it happened solely because my wife and Señor Buck Johnson insist on it. Myself, I don’t think it a good yarn. It hasn’t any love story in it; and there isn’t any plot. Things just happened, one thing after another. There ought to be a yarn in it somehow, and I suppose if a fellow wanted to lie a little he could make a tail-twister out of it. Anyway, here goes; and if you don’t like it, you know you can quit at any stage of the game.

“What oddity is this: Evenings on a Farm near Dikanka? What sort of Evenings have we here? And thrust into the world by a beekeeper! God protect us! As though geese enough had not been plucked for pens and rags turned into paper! As though folks enough of all classes had not covered their fingers with inkstains! The whim must take a beekeeper to follow their example! Really there is such a lot of paper nowadays that it takes time to think what to wrap in it.”

I had a premonition of all this talk a month ago. In fact, for a villager like me to poke his nose out of his hole into the great world is – merciful heavens! – just like what happens if you go into the apartments of a fine gentleman; they all come around you and make you feel like a fool.

And then there is the rhapsodic Gogol.

It was coming on toward evening. Against the eastern mountains were floating tinted mists; and the cañons were a deep purple. The cattle were moving slowly so that here and there a nimbus of dust caught and reflected the late sunlight into gamboge yellows and mauves. [“Gamboge” no less; look it up.]

The hamlet on the upland sleeps as though spellbound. The groups of huts gleam whiter, fairer than ever in the moonlight; their low walls stand out more dazzlingly in the darkness. The singing has ceased. All is still. God-fearing people are asleep. Only here and there is a light in the narrow windows. Here and there before the doorway of a hut a family is still at supper.

To add to the comparison there are White’s cowboys and Gogol’s Cossacks; both tribes are brave, rugged, straightforward and mildly comical.

I wondered whether anyone else had drawn a comparison between Stewart Edward White and Gogol (at least, anyone whose thoughts about it had been digitized), so I Goo-gooed “STEWART EDWARD WHITE” GOGOL. I was linked to an essay by none other than our introducer of An American Omnibus (no one, pointedly, is named as “editor”), Carl Van Doren. Van Doren does not mention White and Gogol in the same paragraph, but he does make a point – well taken – about the difference between literary cowboys, such as White’s, and literary Cossacks, such as Gogol’s and Tolstoy’s.

This is from Carl Van Doren’s Contemporary American Novelists (1900-1920), published in 1922:

[The cowboy] like the mountaineer of the South, has himself been largely inarticulate except for his rude songs and ballads; formula and tradition caught him early and in fiction stiffened one of the most picturesque of human beings – a modern Centaur, an American Cossack, a Western picaro – into a stock figure who in a stock costume perpetually sits a bucking broncho, brandishes a six-shooter or swings a lariat, rounds up stampeding cattle, makes fierce war on Mexicans, Indians, and rival outfits, and ardently, humbly woos the ranchman's gentle daughter or the timorous school-ma'am. He still has no Homer, no Gogol, no Fenimore Cooper even, though he invites a master of some sort to take advantage of a thrilling opportunity.

I assume that Van Doren would have been glad, though a tad dismayed, to learn about the humanization of cowboys by Larry McMurty, Annie Proulx, et. al. I doubt that the imagining of more well-rounded cowboys points to a mastery that earlier Western fiction writers did not possess, but simply is a result of the passage of time and changing literary mores.

(Van Doren mentions White in an earlier paragraph dealing with fictional “red-blooded” Americans – among whose characteristics, incidentally, he lists “their uncritical, Rooseveltian opinions” – by crediting White with “a certain substantial range and panoramic faithfulness to the life of the lumbermen represented in his most successful book, The Blazed Trail.”)

~

The young Sheean was a reporter. He covered the Spanish Civil War for the New York Herald Tribune. In “Revolution” he is in China in 1927, reporting for a syndicate, the North American Newspaper Alliance. (N. A. N. A.’s man in the Spanish Civil War was Hemingway.) Most of “Revolution” deals with Sheean’s experiences in Wuhan, the headquarters of the left wing of the recently splintered Kuomintang. (Chiang Kai-shek headed the right wing.)

Sheean emulsifies the water of the personal with the oil of the historical with a thoroughness that other writers along those lines – the excellent Rory Stewart comes to mind – can’t completely achieve. Sheean’s alert and intelligent presence in Wuhan in 1927 makes it seem that it was a very important place in a very important time, and his respect for and understanding of the personalities involved – even those he does not like very much – make it seem that the people there were very important too: Mikhail Borodin, the Soviet’s éminence grise in Wuhan– whom Sheean does like, almost to the point of veneration, the financial adviser, T. V. Soong, who eventually defected to Chiang, the flamboyant, Trinidad-born apparatchik, Eugene Chen, and Rayna Prohme, who edited the English language newspaper in Wuhan and was Borodin’s propagandist.

Sheean and Prohme became lovers, although that is not something that a gentleman would disclose in a public memoir in 1933. “She was the kind of girl I had known all my life,” says Sheean in “Revolution”, and (or how about and, also but?) her devotion to Communism was a “puzzle” to him. A clue to that puzzle was Dorothy Day. Rayna née Simons, who was from a wealthy Jewish Chicago family, met Day at college (University of Illinois). They became close friends. After the Russian Revolution, she joined the Communist Party and married William Prohme, whom one website describes as a “radical newspaperman.”

Rayna Prohme deserves a bio-pic. In an era when movie producers are scouring history for exciting stories of unconventional, yet cinegenic women from milieus which would allow them to be fashionably costumed, Rayna Prohme is a natural. Here is a description of her by Dorothy Day:

On many occasions I had noticed a young girl, slight and bony, deliciously awkward and yet unself-conscious, alive and eager in her study. She had bright red curly hair. It was loose enough about her face to form an aureole, a flaming aureole, with sun and brightness in it. Her eyes were large, reddish brown and warm, with interest and laughter in them... I saw her first on my way to the university in September. She was the only person I remember on a train filled with students. She was like a flame with her red hair and vivid face. She had a clear, happy look, the look of a person who loved life.... I can see Rayna lying on her side in a dull green dress, her cheek cupped in her hand, her eyes on the book she was reading, her mouth half open in her intent interest.

She was slight, not very tall, with short red-gold hair and a frivolous turned-up nose. Her eyes could actually change colour with the changes of light, or even with changes of mood. Her voice, fresh, cool and very American, sounded as if it had secret rivulets of laughter running underneath it all the time, ready to come to the surface without warning... I had never heard anybody laugh as she did - it was the gayest, most unself-conscious sound in the world. You might have thought that it did not come from a person at all, but from some impulse of gaiety in the air.

Along with Borodin and Madame Sun Yat-sen, when Chiang’s army captured Wuhan Prohme escaped to Moscow. She and Sheean took an apartment together there, but soon afterward she died of encephalitis, thirty-three years old. Definitely, a tearjerker for your consideration.

There is an article on Rayna Prohme in a sort of left-wing Wikipedia, Spartacus International. And there is one in the German Wikipedia, but not in wikipedia.com. I assume that some young German academic did a thesis on Prohme, giving her enough of a German language web presence to be deemed wikiworthy – or perhaps some GDR reference works have been digitized. The fact that wikipedia.com has an article on, for example, (chosen quite randomly), Linda Martín Alcoff, a feminist philosopher whose life’s work (b. 1955) has been only in academia, but that there is no wikipedia.com article on Prohme, whose political activism extended from a close association with Dorothy Day to participating in momentous events in revolutionary China, points up the weaknesses, the failures, of Wikipedia, which I complained about in a previous post.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed