Interesting, first of all, because I hadn’t heard of a third of the writers in it. Here’s the list of authors:

Donald Barthelme

Sylvia Berkman

Borges

Paul Bowles

William Butler

Dino Buzzati

Hortense Calisher

Paddy Chayevsky

Chekhov

Colette

Cyril Connolly

Maria Dermoût

Isak Dinesen

Maurice Duggan

A. E. Ellis

Pierre Gascar

Nadine Gordimer

Marianne Hauser

Ted Hughes

Ionesco

Calvin Kentfield

Françoise Mallet-Joris

P. H. Newby

Patrick O’Brian

Flannery O’Connor

Frank O’Connor

James Purdy

Susan Sontag

Terry Southern

Steinbeck

James Stephens

Dylan Thomas

Nakashima Ton

Anthony West

The stories are presented in alphabetical order by author (except, as is fitting, the first story is Chekhov’s). That gratuitous arrangement also is interesting. There is not the kind of transition from one era to another, one theme, one setting, one mood to another, that often is the solution to fiction collection editors’ struggles toward some sort of cohesion.

Interesting also because, despite a randomly arranged series of stories from what appears to be a diverse congeries of writers, virtually all the stories conform to a certain taste – Morris’ taste, assumedly. They all aim to be about ideas or concepts or codes beyond whatever interest lies in their plots and characters. I know that you can say about any work of fiction. Saying that (“there’s more here than meets the eye”) is what literary critics do as a profession. But most of these stories were written with that extra meaning in mind. If I wanted to be negative and hazy, I could say they were on the didactic side. But that would be unfair. They are somewhat short on action and long on excursus, either directly, in the voice of the author, or via the thought processes of their protagonists. But that’s fine if it’s done well, which it is here, by and large.

Interesting further because, considering the era in which these stories were published, that extra meaning seems somewhat old-fashioned, dealing with moral, ethical, religious issues, rather than the psychological or social issues you would expect from stories published in a major glossy magazine of that era. (The exception to that – the best story in the book – I’ll mention later.)

Some of the authors are known for dealing with big issues. The theology in Graham Greene’s “A Visit to Morin” is more overt than usual. Life’s absurdity is spelled out with as few diversions into plot and character as possible in Susan Sontag’s “The Dummy”. But even the stories by authors one thinks of as less likely to explicitly grapple with issues beyond the tales they have to tell have this trait: Donald Barthelme’s “Florence Green is 81” ends with the narrator, foreseeing the death of a public benefactress which is bound to be to his advantage, belting out a Kyrie from Verdi’s “Requiem”. In Ionesco’s “The Stroller in the Air” a typically bourgeois Ionesco paterfamilias has a vision of life liberated from conventions.

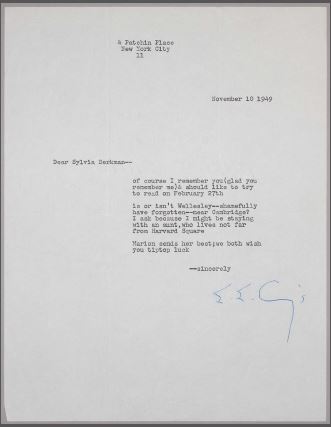

There is something else interesting about the book – not as literature, but as a literary artifact. By and large, it eschews the psychological, existential angst which is found in much of the important American fiction of that era: Mailer, Bellow, Malamud, Singer, Salinger, Roth. Along with the cosmopolitanism of the inclusion of European writers unknown in the states, that avoidance of Freudian angst gives the collection a sort of WASP cachet. Its Jews are token Jews – Paddy Chayevsky, Hortense Calisher, Susan Sontag, Sylvia Berkman (whose Google trail is thin: taught forever at Wellesley, wrote a biography of Katherine Mansfield and a book of short stories, Blackberry Wilderness, the Amazon page for which includes an advertisement for frozen blackberries, recipient of a typewritten note from e. e. cummings

Please do not misunderstand me. I’m not implying that that Morris or Harper’s Bazaar was anti-Semitic. It is simply a matter of taste. Just as a certain taste will avoid Roman Catholic bathos and another avoid Lutheran earthiness, the cultured WASP taste of the mid-20th century avoided Jewish unrestraint, which it (WASP taste) regarded as a kind of tasteless exhibitionism.

These thoughts were taking form in my mind when I came to the last story in the book – last purely because the author’s surname begins with “W” – Anthony West’s “Markie and the Snobs.” It is the best story in the book. It deals with the culture clash, in the Park Avenue set, between the enervated WASP elite and up-and-coming nouveau riche Jews. “Markie and the Snobs”, sensitive, funny and humane, eulogizes the doughty, hopeless resistance of the old America to the incursion of earnest, yet clueless, barbarians and, by extension, the doughty, hopeless resistance of the conservative wing of the literary establishment to the psychologization of literature, a resistance epitomized by The Uncommon Reader’s contents, as well as just its table of contents.

As far as I can see, the Anthony West story is not available in print, outside of The Uncommon Reader, nor as an e-text. ABE Books has a number of copies of The Uncommon Reader for sale for under $4, shipping included (you have to put “Morris” in as a keyword to filter out the zillion copies of a book of the same title by Alan Bennett). If any of this interests you or intrigues you, I suggest you order it, just for “Markie and the Snobs”, if nothing else. (But I am glad to have made the acquaintance, as well, of the Donald Barthelme story and P. H. Newby’s “A Grove in Syria”.)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed