Imagine you were living through a deterioration of Google and Wikipedia and had to look for information from a rash of small quirky start-ups. Their search engines are erratic, their reliability is dubious, and each one seems to have its own specialization. What used to pass as true (that is, “probably pretty accurate”) has broken up into masses of competing data. Information has become soft. Whether Napoleon was born in Ajaccio in August 1768 or in a lightning storm on the summit of Monte Cinto on New Years Day, 1770, becomes as much a matter of opinion as whether he was a tyrant or a savant.

Some users in this hypothetical befuddled period are sticking with Google and Wikipedia even though they have become outdated and spotty. Others settle on default search engines that suit their personal inclinations. A small number build their own search engines which, as you can imagine, severely limit their world views. Occasionally, one of this group is inspired and skilled enough for his or her site to become the default search engine for other users.

Eventually, in twenty or thirty years, all these diverse information sources will merge into one huge Google replacement, but you are stuck in the here and now of internet chaos.

Thomas Gainsborough: Mr. and Mrs. Andrews

Thomas Gainsborough: Mr. and Mrs. Andrews  Benjamin West: Lear and Cordelia

Benjamin West: Lear and Cordelia  John Constable: Wivenhoe Park, Essex

John Constable: Wivenhoe Park, Essex  Henry Fuseli: Adam and Eve

Henry Fuseli: Adam and Eve  J. M. W. Turner: Rain Steam and Speed

J. M. W. Turner: Rain Steam and Speed Eventually, in twenty or thirty years, all these diverse aesthetics will merge into Romanticism, but you are stuck in the here and now of artistic chaos.

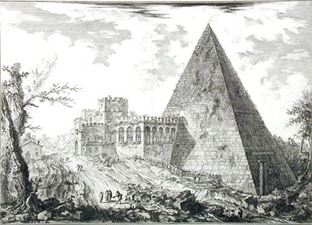

G. B. Piranesi: The Pyramid of Caius Cestius

G. B. Piranesi: The Pyramid of Caius Cestius  Joseph Gandy: Imaginary Ancient Architecture on a River

Joseph Gandy: Imaginary Ancient Architecture on a River  Joseph Gandy & John Soane: Monumental Western Gateway to London

Joseph Gandy & John Soane: Monumental Western Gateway to London Soane and Gandy formed a benign and productive folie à deux, whose view of what was classical architecture eventually went further and further back in time and ranged further and further geographically, until they were able to see the grandeur not only in an Egyptian pyramid, but in an African’s semi-circular hut and even an ant-hill. Although they were not alone in promoting a fantastic universalized architecture, Soane – because of his reputation as a practical architect (his great project was the decade-long construction of The Bank of England) – and Gandy – because of his renown as an architectural draftsman (he was quite the celebrity among aficionados) – were taken seriously.

A transitional period, such as the turn of the 18th century, invites experiments in originality which are not called for and, indeed, are discouraged in periods with more stable artistic protocols. In English painting, the 18th century original who lives on as a master is Turner. Like Turner’s, Gandy’s work was groundbreaking enough to be widely excoriated and affective enough to be appreciated by a happy and influential few of connoisseurs. Unlike Turner, although Gandy spoke eloquently enough to many of his contemporaries, to subsequent generations he was just a curiosity and eventually was relegated, unjustifiably, to the limbo of being of only academic interest.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed