It turns out O’Brien founded the Best American Short Stories annuals, in 1915. He died in 1941, after which Martha Foley took over as compiler and editor.

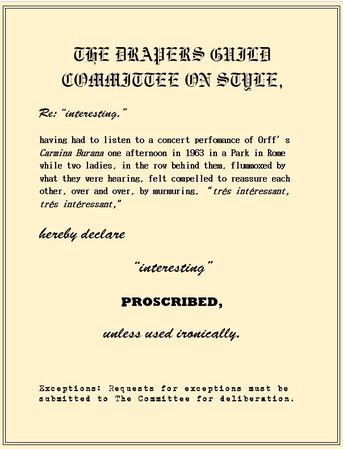

After successfully applying for an exemption from The Drapers’ Guild Style Committee’s proscription against the non-ironic use of the word “interesting I can, with a clear conscience, declare that, along with its pleasures and its longueurs, this book is indeed interesting.

What is most interesting is how the nature of O’Brien’s “best stories” changes over time – style, subject matter, mood, assessment of the human condition. The earliest are still in the late Victorian mode. If it weren’t for its characters’ American names and their American dialect, the Dreiser story, “The Lost Phoebe” (1916), could be another stark tale of human obduracy from Hardy’s Wessex.

In the 1920’s, the writing becomes frothier, the stories’ dramatic hinges become flimsier, less consequential, and they all are humorous – to one degree or another. Dorothy Parker’s “A Telephone Call” (1928) captures their essential frivolity. Even stories not intended as funny are infused by a world-weary irony that from time to time cuts through their gloom.

Then – bang! – comes 1929. The smart set stories (in which even characters with financial woes have Negro maids) vanish.

From 1930 on, O’Brien’s “best stories” take a political stand and convey, to one degree or another, a left-wing antagonism to the capitalist social system.

Faulkner’s “That Evening Sun” (1931) is a compendium of the many and varied inter-racial interactions which add up to racial discrimination as practiced in his neck of the woods. Erskine Caldwell’s “Horse Thief” (1934) is about injustice under the law. Saroyan’s “Resurrection of a Life” (1935) rises to an anti-war peroration. (Saroyan was a master of rich, simple prose but “Resurrection” is one of his lugubrious experiments in stream-of-consciousness.) Steinbeck’s “The Chrysanthemums” (1938) encapsulates the hopelessness of a woman trapped in a man’s world.

Speaking of “best,” one short story in this collection stands out head and shoulders above the others. Those others include Fitzgerald’s “Babylon Revisited” (1931), Willa Cather’s wonderful “Double Birthday” (1929), which sent me to ABE Books to order a Cather short story collection, and Thomas Wolfe’s “Only the Dead Know Brooklyn” (1936). But compared to Oliver La Farge’s “North is Black” (1927), all these others seem dashed off – a little skimpy, a little careless around the edges.

“North is Black” has some similarities with Faulkner’s “That Evening Sun”. Both are deft intimate narrations of an outsider’s view of intense, significant relationships and events. But the world of Faulkner’s black laundress, Nancy, is chaotic; her grasp of it is tentative and febrile – so, then, is the reader’s. The world of La Farge’s Navajo narrator (a world objectively at least as chaotic as that of Faulkner’s Nancy, as his Native culture is subsumed by “Americans”) is so carefully constructed, so clearly illuminated, so carefully detailed, that the reader becomes totally immersed in it.

Immersed to this extent: When La Farge’s Indian brave tells us “A lot of time went by this way,” we of course understand that his “a lot of time” could be weeks or could be months, but we are so committed to his mindset that whether it is weeks or months does not matter, but only that it was a lot of time as far as he was concerned.

Ostensibly, “North is Black” is a story of unrequited love, but its denouement is based on the failure of the protagonist, who has seemed so wise, to fathom the subtleties of the similarities, as well as the differences, between his culture and that of the “Americans.”

I took my money and went in where they were. I said: “Here is your money, that I have won at cards. I did not know you did not cheat, until I heard you talking. The Americans who played with us always cheated. Now I will not cheat. That is my word. It is strong.”

Northern Maiden’s brother said, “The Indian’s all right.”

The other one, who knew about Indians, said: “Yes, what he says is true. He will not cheat any more. Let him play.”

Charlie was angry, but he was afraid to say anything.

La Farge was an anthropologist as well as a writer. There is not one false note in his Navajo’s narrative, not one literary darling, not one hint of a European sensibility. Because of that, or despite that, “North is Black” is a masterpiece.

Some more things I found interesting about 50 Best American Short Stories 1915-1939:

• Not a few of the stories – most notably “The Half-Pint Flask” by Dubose Heyward (1927) – take what the authors surely thought was a pointed, progressive stance on racial equality. However, with the exception of the Faulkner story, their arguments for racial justice rely on endearing and patronizing “Negro” stereotypes which would, today, put them beyond the pale. I am sorry to say that the last story in the book, Richard Wright’s “Bright and Morning Star” (1939), about poor black Communists, suffers from the same banality

• Children are the protagonists of a surprising number of the stories – often as first person narrators. Hemingway’s “My Old Man” (1923) is one of the better of them; James T. Farrell’s “Helen, I Love You” (1937), one of the worst.

• And a surprising number are first-person narratives in the vernacular. Some opening lines:

Sometime away back in Seventeen and Seventy, on the trek outa Virginia into Kentucky, one of Ike’s ancestors saved one of our’ns life at the cost of his own, and ever since then our kin and his’n has sorta stuck together. – Ike and Us Moons, Naomi Shumway (1933).

Well, R. A., I wish you could of been out to Rotary today. You certainly missed a treat. They pulled of a pretty cute little stunt, and I’m right here to tell you it would of give you something to think about, you old potwalloper, you! – A Pretty Cute Little Stunt, George Milburn (1931)

I didn’t steal Lud Moseley’s calico horse.

People all over have been trying to make me out a thief, but anybody who knows me at all will tell you that I’ve never been in trouble like this before in all my life. – Horse Thief, Erskine Caldwell (1935)

Thomas Wolfe’s “Only the Dead Know Brooklyn” (1935) might make those of us who gave up on Look Homeward, Angel wish Wolfe had taken the road more traveled by.

Dere’s no guy livin’ dat knows Brooklyn t’roo an’ t’roo, because it’d take a guy a lifetime just to find his way aroun’ duh f_____ town.

• Willa Cather’s pithy portrait, in “Double Birthday” (1929), of a bohemian household in Pittsburgh – as genteel and proper folk as the bourgeois who surround them, their bohemianism resting solely on their disinterested attitude toward wealth and position – is fresh and enlightening. I can’t remember coming across people like the Englehardts in Wharton or James. Hmmm – maybe in The Bostonians.

• Walter D. Edmonds’ “Death of Red Peril” (1929) is one of the funniest stories I’ve ever read.

• I had never read anything by Kay Boyle, but if “Rest Cure” (1933) is anything to go by, I won’t bother. It is a mean and nasty little nothing about D. H. Lawrence in his final illness. She doesn’t mention Lawrence by name, but it was clear to me that Lawrence was the subject of her travesty even before it was confirmed in O’Brien’s note in the book’s handy-dandy biographical appendix.

• Fitzgerald is represented by “Babylon Revisited” (1935) – well-written, but gooey in its autobiographical sentimentality.

• The most embarrassingly bad story is Tess Slesinger’s “A Life in the Day of a Writer” (1935), which begins, “O shining stupor, O glowing idiocy, O crowded vacuum, O privileged pregnancy, he prayed, morosely pounding x’s on his typewriter.”

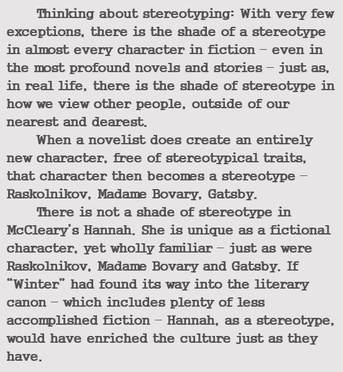

The most unusual story – meaning that its content is something I had not encountered before – is “Winter”, by Dorothy McCleary (1934). McCleary sensitively, affectively describes the morning conversation of a middle-aged couple, Hannah and Thomas, from the moment they awaken together in bed. Without rushing in with any sort of trumped-up exposition, McCleary takes her time and waits for an occasional word, naturally dropped here and there, for it to slowly emerge that Hannah and Thomas don’t know each other.

At first we think Hannah is a prostitute then, again, it slowly emerges that she’s an eccentric barfly who likes to bring men home with her. Thomas is a vagrant, beaten-down, down-at-the-heels, clinically depressed (we’d say today) by remorse over having abandoned his family years earlier. The drama of “Winter” is the conflict between Hannah’s efforts to cheer Thomas up, and Thomas’ resistance.

To give you an idea of McCleary’s remarkable patience, when it comes to avoiding exposition: For the first thirteen of twenty-six pages, McCleary refers to Thomas only as “he.” We assume she is conforming to the often annoying fictional convention of leaving characters un-named, in order to sort of universalize them. Then:

[“He” is speaking about his family] “...No, my girl looked like an angel. Did you ever read a little book called Editha’s Burglar? There was a picture in it that anyone might take for my Editha. That’s why we named her Editha.”

“That’s a pretty name, do you know it?” said Hannah.

“It is, isn’t it? It’s a beautiful name. Editha. Editha. I believe in giving girls pretty names, and boys strong names. It makes men of them.”

“Yes, and my sister did just the other way. She named her boy, the one that died, Archiduke. But the two girls she named Ella and Hannah, the youngest one for me. And I think my name’s too plain, don’t you? I never was pleased with my name. I wish they’d of called me Phyllis – that’s my favorite name for a girl.”

“My name,” he announced impressively, “is Thomas Quinn O’Hagerty!”

“You’re an Irishman, by God!” said Hannah, running her hand affectionately over his hair.

"Winter" is a beautiful story.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed