He also was mentally unbalanced. Mentally ill? I’m not sure. Jeffrey Meyers, the author of a biography of Lewis I just finished reading, The Enemy, sometimes calls Lewis’ problem “persecution mania,” sometimes “paranoia.” He was not a paranoid schizophrenic, though. There are three or four instances where he is reported to have heard voices or have had hallucinations, but these do not seem to have had the profound effect on him that auditory and visual hallucinations have on schizophrenics.

The onset of schizophrenia usually occurs in a person’s twenties. Lewis’ paranoia seems to have been set off (never to be reigned in) when he was thirty-one, when Roger Fry – if Meyers’ recounting of the story is true, which it seems to be – deliberately, almost criminally, did Lewis out of an important commission.

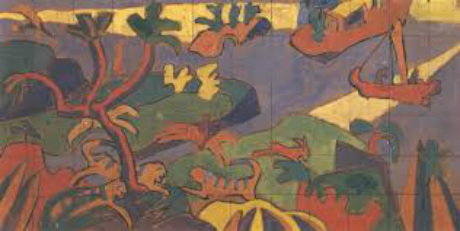

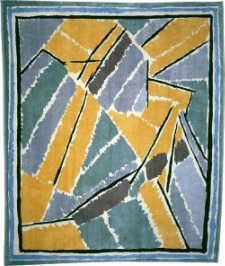

Lewis, at the time, was an up-and-coming impoverished artist. Fry, sixteen years older than Lewis, a prominent artist and critic, was the Bloomsbury Group’s hetman for the visual arts. (It was he who coined the term “post-impressionism.”) In 1913 Fry founded a collective, the Omega Workshops, which aimed at integrating visual art and design. Lewis, who had been friendly with Fry and other Bloomsbury gang-members, was happy to become part of Omega, even though his paintings were not in the post-impressionist style of Duncan Grant, Vanessa Bell and Fry.

(Wyndham Lewis' murals for the nightclub -- typically for his blasted career -- are lost.)

Gore was otherwise engaged and recommended Wyndham Lewis. Gore also suggested that Roger Fry should provide Omega Workshops furniture for the room. The Daily Mail critic was fine with both suggestions. It was an important commission, so Gore hurried around to the Omega Workshops with the good news. Neither Lewis nor Fry was there, so Gore relayed the news – that Lewis would be doing the decorations, Fry providing the furniture – to Duncan Grant.

Grant later said he “may have forgotten” to relay the message to Lewis. The message reached Roger Fry, though, who phoned The Daily Mail, and ended up getting the commission for the decorations, as well as for the furniture. The Daily Mail art critic soon made it known that the commission for the decorations had been meant for Lewis. Fry refused to relinquish it and, as a sop, offered the design of the room’s mantelpiece to Lewis. Lewis was furious. It was this incident that seems to have pushed him over the edge into his lifelong paranoia.

Like most paranoiacs, Lewis’ mania had its stealth aspects – in restaurants and other public places, he would make sure always to sit with his back to the wall – but mainly it took the form of public vituperation. Most of his novels and virtually all of his non-political non-fiction writing were devoted to lambasting prominent figures in the art world – especially those who had helped him out in some way. (“If Wyndham Lewis asks you to lend him a hundred pounds,” Ford Madox Ford once said, “Don't do it. He'll never forgive you!”)

He was a far better artist than a writer, but prose was an outlet for his eruptive anger, his wrath at Bloomsbury, especially the Sitwells, and the cultural elite. He spent much more time and effort spewing out unsubtly satirical invective than on his painting.

His self-sabotaging went beyond embittering people he knew. He went on to alienate anyone in the public who might have bought his books and his art with his hagiographic 1931 book, Hitler, which referred to Hitler as “a man of peace” and presented the Nazis as Western culture’s bulwark against Communism. He recanted, too late, in his 1939 book, The Hitler Cult. In the same year, he also published a book condemning anti-Semitism, but the imp of self-sabotage prompted him to title it: The Jews, are they Human? (You’d think someone at George Allen & Unwin would have set right that faux pas.)

Pound and Eliot remained stalwart supporters; the former until his alliance with Fascism made his support onerous, the latter right up to the very end, even though both had been at the receiving end of some of Lewis’ ham-fisted salvos. Eliot always maintained that Lewis was a great prose writer – an opinion, by one of the last century’s best literary critics, that puzzles me. I’ve looked into more than one of Lewis’ fifty books, usually because their striking covers stood out among the same-old same-old on the shelves of used bookstores. I found them pretty much unreadable.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed