Die Elfenkönigin Kuss, the Fairyqueen’s Kiss, was a brothel on Seilerstrasse, in the St. Pauli district. Like most brothels of that era – not just in Germany, but everywhere European culture had made inroads, from Deadwood to Budapest, from Sydney to Paris, from Macao to Moscow – the ambience of Die Elfenkönigin Kuss, its mise en scène, was the romantic and sentimental fantasy of domestic life aspired to by the upper bourgeoisie.

The brothels of the early 19th century emulated the settings of the new bourgeois domestic tragedies, Schiller’s Intrigue and Love and Landois’ Sylvie, for example, on the stage, and in literature, such novels as de Raabe’s Chronik der Sperlingsgasse and Stifter’s Nachsommer. Into the ideal bourgeois life, which previously had been staid and careful, these works injected sentimental, romantic and erotic license. Husbands and fathers who a generation earlier either would have avoided brothels or treated them as furtive pleasures, could visit one without violating the comfortable and respectable personae which they thought of as their identities.

The parlor of Die Elfenkönigin Kuss, where the women would display themselves for sale – or for rent, rather – was a large rectangular room, broken up into nooks tucked behind folding tapestry screens depicting scenes of medieval merriment and piety.

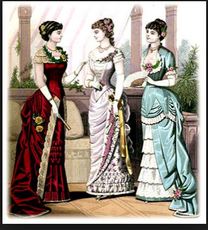

The prostitutes, or if you prefer, sex workers, of Die Elfenkönigin Kuss dressed in the style of a wife of a city councilor about to accompany her husband to a party at the home of a chief magistrate.

The transition from polite society to the arousal of erotic passion was accomplished smoothly and with propriety, once the couple had withdrawn into the bedroom, as the prostitute choreographically removed her clothing, one garment at a time, starting with the gloves. The customer’s increasing amorousness was greeted with a display of shy acquiescence and requests for the fulfilment of his more imaginative wishes would elicit a genteel discomposure that gradually was overcome by an anticipation of pleasure.

It is not in Brahms’ frequent use of folk themes and dance hall numbers that the influence of Die Elfenkönigin Kuss in his work can be found – all the composers of the time drew on popular sources – but in his expression of the heightened bourgeois sentimentalism that permeated Die Elfenkönigin Kuss. This hyper-sentimentalism finds its fullest expression in Brahms’ chamber works. Its evocation of bourgeois passion as it was idealized in a brothel is another marker of the end of the Goethean phase of the Romanticism and a next step in the combining of the aristocratic and popular styles which Erich Auerbach, in his great Mimesis, sees as the continuing progress of art (although Auerbach did not put it in those terms, exactly).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed