The neurologist George Miller Beard, in his memoir, American Nervousness, describes the feeling as “a joyous sense of release.”

My next question was: what should I call this new startle reflex? With a joyous sense of release it dawned on me that, like an explorer who has discovered a mountain or an island, like an astronomer who has discovered another moon of Saturn’s, like an horticulturist with a new hybrid, I could name it anything I wished. Fortunately, I was able to shake off the temptation and refrained from naming it Liza-Hubert Dyskinesia, after my wife and son, or New London disorder, to please the mates who sailed with me on the gunship New London during the War, or Van Agthoven’s Tic, after the professor of neuroendocrinology to whom I abandoned my innocence – or, for that matter, naming it Beard’s Syndrome. No, I let scientific observation be my guide and named the previously unknown pathology Jumping Frenchmen of Maine.

Despite the freedom of expression on offer, scientific nomenclature seldom becomes more imaginative than honoring a particular person or place or thing – Alzheimer’s Syndrome, Lyme Disease, Peacoat Virus. The most creative fields, when it comes to nomenclature, are astronomy, psychology and zoology, with the most sophisticated examples found in the naming of zoological collective nouns.

A murmuration of swallows, a pride of lions, a murder of crows – names entertaining enough to have been made into a best-selling book. I suppose everyone, if they never owned a copy of James Lipton’s “An Exaltation of Larks,” at least browsed through it at the bookstore across the street from the movie theater while waiting for the 5:00 show to get out.

Interestingly, in the convivial game of zoological collective nomenclature, participants have been careful not to aim

We could speculate about the cause of this restraint – political correctness? to avoid provoking a scathing response from of the all-powerful Sociology Department? an irrational, superstitious fear of provoking the wrath of God? – but let’s not.

Whatever its cause, the failure to assign to one’s own species the kind of thoughtful collective noun which enlivens the study of baboons and bats and bears all comes down to a failure of nerve.

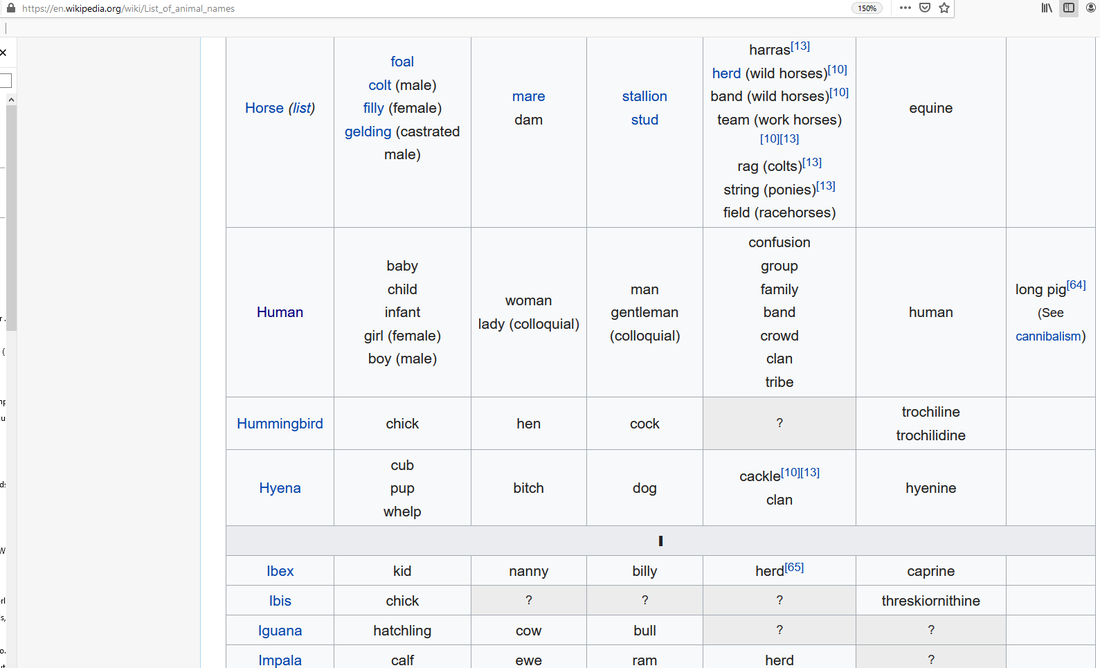

We attempted to rectify the omission but, I’m sorry to say, our effort failed after less than 24 hours. Wikipedia, March 5, 2020, c. 5:00 PM:

“Crowd” does evoke a particularly human conflict of instincts: the instinct to assemble together vs. the instinct to resist, or at least fulminate against, any invasion of one’s personal space.

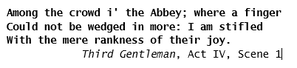

“Crowd,” whose first use as a noun was by Shakespeare in Henry VIII (1612), is a coinage from “crowded” – ceoʤyʤ in Old English, deriving from the Old Norse of Faro Island’s cœðdøyhraf, designating a cairn in which more than one body is buried.

Although admittedly evocative, because of its origins the word “crowd” tends to favor the oppressive side of assemblages of humans, ignoring their liberating potential. The conflict between society and the individual is better expressed by the collective noun, “confusion.” Unhappily, our suggestion was rejected by Wikipedia’s editors.

There already is a grass roots movement afoot to make “confusion” the go‑to collective noun for humans. We urge you to join in. It actually does not take much effort. In fact, it’s fun. When you next find yourself about to say something like “Let’s grab a drink and join the crowd” or “There’s a crowd of reporters on the front lawn” or “two is company, three’s a crowd” substitute “confusion” for “crowd.” You will find, in every case, that the change in nomenclature makes whatever situation you are in less daunting and more amusing.

Some practice exercises:

There was a difference of opinion about the size of the confusion attending the inauguration.

The confusion’s enthusiasm for the assassins turned to vitriol under the sway of Antony’s subtle and measured oratory.

The effect of violent dislike between confusions has always created an indifference to the welfare and honor of the state.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed