I had only a vague notion of what Carl Jung was all about – archetypes, the collective unconscious, the betrayal of Freud; I loved Hayman’s biography of Proust; I thought I was in for a treat.

Not to be. Hayman’s A Life of Jung is not very good. I read it through, for its biographical details and its account of Jungianism, but became more and more annoyed. It became clear, one chapter in, that Hayman disliked Jung – a difficult mindset in which to write a successful biography. Hayman’s attitude toward Proust was one of indulgent affection, and it made for a nicely tuned book.

For some reason, probably because he’s immersing himself in the world of psychiatry, Hayman uses pop-psychology to analyze Jung’s words and actions; something he didn’t do in his Proust book. Besides the fact that pop-psychology is a mainly Freudian exercise, considering Jung’s deep and detailed probing of human behavior, and Freud’s, and their colleagues’, Hayman’s explications come off as shallow and catty.

Like a son telling his father he has done nothing wrong – and even if he has, contrition has already hurt him more than punishment could – Jung [in a letter to Freud] refers three times within four sentences to hell and the devil.

Naturally, he felt ambivalent towards people who year after year counted on him for emotional support.

On this trip to the USA, Jung did not have to share the limelight with Freud, and being lionized helped to consolidate his self-confidence.

There is little difference between these remarks and something like, “Stepping ashore at Missolonghi, Byron sensed a chill of foreboding.”

Hayman’s book was published in 1999, so he and his editors cannot fall back on the excuse of customary practice to explain the patronizing misogyny behind Hayman’s habit of identifying his male characters by their surnames and his female characters by their given names.

Jung had a habit of turning his female patients into Jungian analysts. Some of them were very good at it – so good, in the case of Toni Woolf (patient, then analyst, author – Studies in Jungian Thought – and for a number of years the third in a Jung domestic ménage), that some patients preferred to consult her rather than Jung. Still, throughout his book, Hayman refers to her as “Toni,” while to males who appear briefly and then vanish, for example, rich, silly American patients and the husbands of rich, silly American patients, he does the courtesy of referring to them by their surnames.

Hayman’s Jung was worth reading, though, if only for one striking revelation. One evening in 1902, William James dropped in on Stanley Hall, the president of Clark University, in Worcester, Mass., and there met Hall’s houseguests, Jung and Freud. On imagining this strange encounter, a door in my mind, between the New England compartment and the Viennese compartment, swung open.

While Hayman goes into great detail about many aspects of Jung’s personal life (nothing wrong with that; that’s what biography does), the most intriguing story he tells he leaves hanging at just this:

In 1901, [Jung] wrote to Emma [Rauschenberg], asking her to marry him, but she told him she was engaged to a man in the village. Her mother liked Jung enough to arrange a meeting in a Zurich restaurant, where she explained that Emma was not engaged. Inviting him back to the estate, the Rauschenbergs sent their horse-drawn carriage to collect him from the railway station. He again proposed to Emma, and this time she said yes.

It’s the plot of a Chekhov short story. What tender and pathetic dynamics drove this little bourgeois comedy? Hayman, who usually does not balk at a little motivational speculation, has nothing to offer. Occasionally, he tries to grasp and convey Emma Jung’s feelings and her attitude towards Carl and their marriage; knowing, or even making an educated guess about, what occurred between her refusal and her acceptance back in 1901 would have helped.

I have become a huge Edna O’Brien fan, thanks to my friend Dennis who keeps lending me her books, so you’ll have to excuse me if I gush. Except for Philip Roth, I can’t think of any other living writer in English who churns out book after book after book, of her caliber. Ian McEwan’s novels are thin, dry things in comparison.

I get the impression that O’Brien is considered as a bit disreputable, in literary circles and/or academia. Maybe that’s because of her persona, which is a tough cookie – more Mae West than Virginia Woolf. It is understandable how such irreverence might get up highfaluting noses. How does this sharp, orange-haired, bejeweled bitch get to be the one to write such colloquially exquisite, sensitive prose, with the knack, which Jewish and Irish writers seem especially able to pull off, of emulsifying comedy and tragedy so thoroughly that readers never know whether to laugh or cry?

O’Brien loves James Joyce – Joyce, the writer, that is. She makes no judgments about Joyce, the man; he’s just a character, grist for storytelling. No, I take that back. O’Brien is aware that there is a sorry judgment that could be made, but she excuses Joyce’s ill-treatment of his family, his friends and his supporters (notably the downtrodden Harriet Weaver) on the grounds that he is an obsessed artistic genius.

O’Brien has offered a similar excuse for her own character flaw, her bitchiness – not going so far as to proclaim herself a genius, but anointing herself as an obsessed artist. A further reason for all those writers and academics who, true to the modern mode, are thoroughly polite, thoroughly domesticated, to resent her.

...After months of begging and cajoling Budgen obliged by coming in person to Paris. The revels got headier. They stayed out late, still later, Joyce insisting when the bar closed that they be admitted to an upstairs parlor and in the small hours when they did make their way home, Joyce in his straw hat and cane performed his Isadora Duncan impersonation, a matter of whirling arms, high-kicking legs, and grimaces which Budgen likened to the ritual antics of a comic religion. They laughed a lot, wakened the neighbors and returned to an irate Nora Barnacle shouting out the window and demanding that these revels stop. They didn't. They couldn't. Nothing could dampen Joyce's abundance of spirit and laughter during those his richest and most exhaustive years. In one of these night fracases, Nora told him that she had torn up his manuscript and it sobered him enough to ransack the apartment and find it. The book "ist em Schwein," she said. Carousing was only part of the saga; there was another side to him that very few saw, hurrying from one tuition job to the next, or one creditor to the next, not laughing, not smiling but as the novelist Italo Svevo noted, "locked in the inner isolation of his being."

Details are O’Brien’s métier. She doesn’t care much about the big picture. In one chapter of her book, Joyce may be in Trieste; in the next, Zurich; then Paris; then he’s back in Trieste. The reader has no idea why one city rather than the other or even when one city rather than the other. It’s as if Joyce owned a private helicopter that transported him, at the drop of a hat, from one miserable slum hovel to another. O’Brien’s novels often are similarly vague about why and how the narrator finds herself in one locale rather than another. All locales are poignantly and meticulously described, of course.

O’Brien’s critical take on Joyce is that he was a mad virtuoso of language. If that does not describe someone who took it upon himself to write Finnegan’s Wake, I don’t know what does. O’Brien, too, is a virtuoso of language – but not mad. Her goal is intimacy, not grandeur.

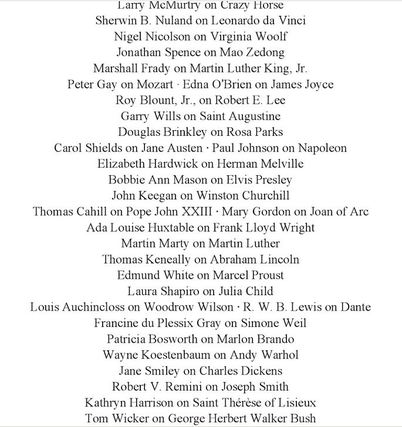

Edna O’Brien’s James Joyce is a compact (178 pages), handsome duodecimo hardback. It is a pleasure to look at and a pleasure to hold. It makes you want to own more of like it, subject matter aside. It is part of the Penguin Lives series. Only ten remain in print; only one, Nigel Nicolson’s Virginia Woolf, maintains the series’ original classy design. If this were the 20th century, a uniform series of biographies by a major publisher would remain in print until it was finished and for some time afterward, at which point the complete series, with a bookshelf to fit, could be purchased.

Penguin Lives offers biographies written by writers, not – as they usually are – by academics or reporters. "Mary Gordon on Joan of Arc" is a particularly brilliant choice. I see two or three whose content (and that includes the author) suits my taste, that I might check out ABE Books for. Still, it is the books in this series, as objects, that are attractive. I chose those two or three in the same spirit with which a collector of early Delftware depicting monkeys might browse through a couple of stacks (or web pages) of Delft plates.

O’Brien’s James Joyce begins with a short introduction by Philip Roth. I haven’t read it – yet, or maybe ever. Introductions can be spoilers, and not in only the word’s current meaning as a buzzword, but in its general sense.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed